From Los Angeles to Language Agents, from LA to CoALA.

What was the first thing anyone was thinking about when hearing LA in the 20th century? Undoubtedly, Los Angeles. By the end of this century, possibly this decade, the first thing anyone will think about will be Language Agents. Sorry, city of angels. On September 5th, 2023, researchers from Princeton University published a foundational paper on arXiv: Cognitive Architectures for Language Agents (CoALA).

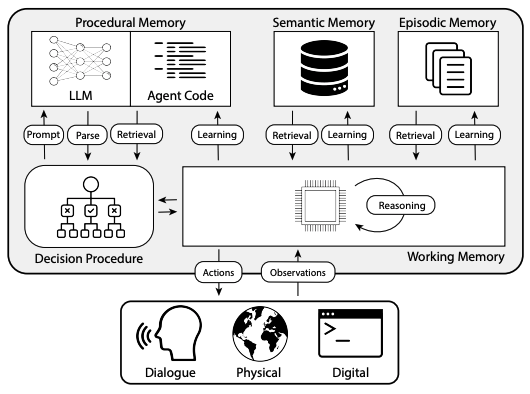

Language Agents (LA) are systems that leverage Large Language Models (LLMs) to interact with the world. The work introduces a standardized, general architecture for Language Agents. Built on top of cognitive science and symbolic AI, CoALA presents a conceptual framework that organizes existing agents and sets conventions for naming the same thing the same way; as well, it suggests the way forward for a modular architecture that will enable standard protocols definition and open source implementations to be released and adopted at scale.

Table of contents

Introduction

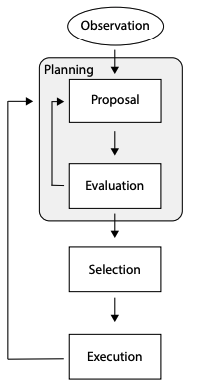

Agents that need to interact with the external world in a semi-autnonomous way do so in two main phases: planning, and executing. The main procedure is a loop that receives tasks or signals from the external world, and selects the next step according to the decision-making logic implemented in the Agent’s source code.

Through Reasoning and Retrivial, the Agent plans the actions needed to achieve its tasks. Planning usually consists of suggesting, evaluating and selecting one or more actions. Actions can either affect the external world - and in this case it is called Grounding, or can update different memory components - and in this case the Agent is Learning.

At this point, we could introduce all the different modules at high-level and explore the history of cognitive science, but I will surely do a much worse job than the authors’, so if you are curious you read the full paper and give it the time it deserves. Here we will be more concise and go straight presenting the different components.

Memory

As LLMs are trained on a static dataset and are stateless, several kind of conceptual memories are designed and used for different scopes.

Memory can be further split into two main categories:

- short-term memory: named Working memory, it keeps track of the context, status, variables, and all the releant data structures of the current execution that need to persist across different LLM calls and other actions. It can be seen as the equivalent of a RAM.

- long-term memory: groups Episodic, Semantic, and Procedural memories, it is the storage of Language Agents. Information stored in long-term memories persists after the task is completed.

Agents interact with memories through all the internal actions, that is all but Grounding:

- Retrieval: read-only from one or more long-term memories

- Reasoning: update the short-term memory

- Learning: update one or more long-term memories

Working memory

The working memory is the central hub connecting LA components. The input to actions and LLM calls is always a subset of the working memory. Responses and other inputs received from the external world are parsed and stored in the working memory at first, before being used in the following actions.

Taking the original ChatGPT as an example, the Working memory was the prompt instructing the model to reply in a certain way, information about the model itself and OpenAI, the knowledge cut-off date, and the conversation history.

Episodic memory

The episodic memory is used to store experiences from earlier decision cycles. This memory is retrieved in the reasoning step to support planning, and is updated using some parts of the Working memory during Learning actions.

Semantic memory

The semantic memory contains the knowledge about the world and the Agent itself. It is the memory accessed in Retrivial Augmented Generation (RAG) pipelines. This memory too can be updated from the Working memory as form of learning.

As an example, it can be the Knowledge Base of a company’s Customer Service department. Nowadays, it is used by human agents answering phone calls and messages. Tomorrow, it will be the primary source of information for Langauge Agents specialized at Customer Service jobs.

Procedural memory

The procedural memory is made of two parts: an implicit memory stored the LLM weights, and an explicit memory stored in the Agent’s code. The Agent’s code procedures can be further divided into code implementing actions and code implementing decision-making itself.

Some further reflections should be made; as implicit and explicit memory differ a lot in terms of implementation, complexity of update, explainability, usability, and kind of knowledge represented, it might be beneficial to split them into two separate memory classes. De-facto, they are.

Likely, the authors grouped them under the same umbrella for two main reasons:

- it is the only memory that must be initialised by the Agent’s designer

- it is by far the riskiest memory to be updated by the Agent autonomously; it might both lead to bugs and unaligned behaviours.

I expect designers to split the Procedural memory into read-only and read-write modules. It might make sense to let the agent update or propose changes to some part of the procedural memory.

Actions

The ability to affect both the internal and external environments is what differentiate a standard LLM used as standalone component or in a RAG pipeline from a Language Agent. This occurs through different actions.

Grounding actions

Under Grounding actions CoALA collects all the actions executed against the external environment. The feedback received from the environment is used to update ONLY the Working memory. Grounding actions can be divided into:

-

Physical: actions that require some physical execution, like controlling a robotic arm, or steering the wheels of a self-driving car. LLMs can be used to generate plans for actions executed in the real world. Vision-Language models are a key enabler in this domain.

-

Dialog: actions that enable interaction with humans and other Agents. Those actions can have different goals: from asking for feedback to entertaining, from seeking specialised help from other Agents to brainstorming and collaborating. At the time of writing, Microsoft has just released AutoGen, an open source “framework that enables the development of LLM applications using multiple agents that can converse with each other to solve tasks. AutoGen agents are customizable, conversable, and seamlessly allow human participation.” I will definitely give it a shot in the coming days.

-

Digital: actions to interact with the digital world. This includes playing games, navigating websites, accessing databases and using APIs, executing code, triggering pipelines, and anything else you can think of in the digital realm. Tools from LangChain and ChatGPT Plugins are examples of Digital actions.

Retrieval actions

Retrivial actions are all those actions that read from long-term memories and write to the Working memory. Retrivial can be rule-based, sparse, dense, or a combination of those.

I think here there is huge room for improvement. By supporting retrivial with reasoning, Agents can combine Digital actions and “pure” retrivial to update the Working memory with all and only the information needed, restructured in the most efficient manner to solve the task at hand.

Haystack pipelines are a common way to implement RAG pipelines.

Reasoning actions

Reasoning actions process the Working memory to generate new information. Most often, this is done providing a subset of the Working memory as a prompt for the LLM. The output is then parsed and used to update the Working memory accordingly.

Reasoning can support all other actions.

Learning actions

Until yesterday, or perhaps today, learning actions consisted of updating the Semantic memory, manually tweaking the explicit Procedural memory, or updating the implicit Precedural memory by fine-tuning the LLMs. The new wave of Agents will ALSO use decision-making and reasoning to learn.

Learning actions encompass all actions that update the long-term memories:

- Episodic: store relevant experiences, implicit and explicit feedback and outcomes observed, and more.

- Semantic: store reflections, update World knowledge using knowledge acquired as outcome from other actions, restructure the semantic knowledge in an optimised way, and more.

- Procedural (implicit): Automatically fine-tune one or more LLMs during the Agent’s lifetime. This comes with the risk of degrading the LLM performance and/or being costly, so it should be handled with care.

- Procedural (explicit): Updating the Agent’s own code comes with major risks, but there are possibilities worth exploring. Agents could update reasoning (by tuning prompts based on feedback and experience), grounding (by generating new code, tools, libraries, etc to interact with new environments: for me, this is a key aspect of truly autonomous agents), retrivial (exploring new retrivial algorithms, a heavily understudied domain with huge potential), but also learning and decision-making itself (this would make them very human, comes with huge risks and complexity but also provides unprecedent flexibility).

LA can select from several learning procedures. This allows it to be cheaper, faster and more robust than standard LLM fine-tuning. Furthermore, different learning steps compound to a generalised self-improvement whose potential is hard to predict. Last, it is much easier to modify and delete knowledge, the so-called unlearning process. For example, if a LLM answers in a certain way because of the implicit knowledge of its parameters, the Agent can learn to phrase the prompt to compensate the wrong implicit knowledge without retraining or changing LLM altogheter.

Decision-making

Decision-making is the process of selecting the next action to execute. It is the core of the Agent’s code, and it is the most important part of the Agent’s design. In each cycle, either planning (Reasoning + Retrivial) or execution (Learning or Grounding) is performed.

Planning

In the planning phase, actions are proposed, evaluated, and selected. Multiple planning phases can be executed in sequence, to simulate different scenarios before executing external actions.

- Proposal: Generate one or more candidate actions (using LLM reasoning and retrieval)

- Evaluation: Assign a value to each candidate action (using heuristics, perplexity and other LLM metrics, learned rules, LLM reasoning, …)

- Selection: Select the action with the highest value (using softmax, argmax, max voting, …)

An underexplored approach is to use LLMs to generate a textual explanation, and then let the LLM also decide which ation to proceed with, considering its own textual explanation of the proposed actions.

Execution

The selected action is executed in the external environment. The feedback is parsed and stored in the Working memory. This will ignite another cycle.

Overview

After looking closer at each module, it is worth making a step back again and look at the big picture. The following diagram shows the different modules and their interactions.

Actionable insights

The paper comes with a bunch of actionable insights that I will summairse here.

First and foremost, Agents should follow a systematic, modular architecture. When designing a new Agent, CoALA can be used to evaluate what components are needed, and what can be skipped.

Reasoning insights

- Framworks like LangChain and Haystack can be used to define high-level sequences of reasoning steps.

- Output parsing (e.g. OpenAI Function Calling) can be used to update Working memory variables.

- Good working memory modules should be defined and built.

- Reasoning specific LLMs should be fine-tuned!

Retrieval insights

- Use manuals / textbooks to empower agents.

- Integrate retrieval and reasoning by interleaving memory search and forward simulations

Learning insights

- In-context and fine-tune learning are still very valuable!

- Restruscture and store knowledge from experience, observation and feedback.

- Write or modify Agent code: this is the most powerful and risky learning action.

Grounding insights

- Define a clear and task-suitable actions space

- Consider the risks of external actions

- Ablate the action space for worst-case scenario!

Decision-making insights

- Write and execute simulations to evaluate different plans

- Adaptively allocate planning and execution budget by estimating respective utilities

- Digital realm allows reset and parallelism, use it!

- The human reasoning methodology might not necessarily be the most optimal one for LAs in all cases.

- Agents should schedule learning tasks for their own “personal” development.

Conclusions

The paper is a great starting point for the development of a standardised, modular architecture for Language Agents. It is a must-read for anyone interested in the field, and I am looking forward to see the first implementations of CoALA.

Might that be Gilbot, my personal digital assistant that has replied to LinkedIn DMs on my behalf in the last weeks? Who knows.

Last, as Software and Hardware have grown together in the last decades, LLMs and Agent Design should and will co-evolve too! What an exciting time to be alive.